QUICK CONSERVATIVE | By Jessica Walters

How Does China's Social Credit System Work?

Click here to listen to this article via podcast. A summary video is also available here.

Have a vague idea that China’s social credit system is bad, but don’t really know much past that? Join the club!

The idea that China assigns citizens scores based on social behavior – ranging from volunteering to jaywalking – has sparked fears of an Orwellian dystopia. But how does the system actually work? And is it really as bad as it sounds?

To find out, I pulled primary source documents from China and poured over dozens of reports from think tanks and researchers. But while the details below clear up a lot, at the end we’re still left with two schools of thought:

Those who consider China’s program “the most ambitious experiment in digital social control ever undertaken” and those who claim “what is often misrepresented in the West as 1984 and Black Mirror rolled into one is only Beijing’s latest attempt at finding a one-size-fits-all solution to domestic governance.”

Keep reading to decide for yourself.

Jump To Section:

What Is China’s Social Credit System?

According to government documents, the system’s goal is to strengthen sincerity (or trustworthiness) in government affairs, commercial/business practices, social interactions, and law enforcement/judicial proceedings. In 2011, then-Premier Wen Jiabao stated:

[The social credit system] provides a good moral guarantee for the reform and development of the socialist economy, politics, culture and society.

Premier Wen Jiabao (2011)

The South China Morning Post concisely describes the system as “a set of databases and initiatives that monitor and assess the trustworthiness of individuals, companies, and government entities.” Citizens are assured that comprehensive monitoring will cut red-tape and improve government services and overall safety. However, Samantha Hoffman, non-resident fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, has a different perspective, claiming the social credit system is a tech-enabled automation of Mao’s Mass Line (a term used to describe how the party managed society).

According to Hoffman:

In Mao’s China, the Mass Line relied on ideological mass mobilisation, using Mao Zedong’s personal charisma, to force participation. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) could no longer, after the Mao era, rely on ideological mobilization as the primary tool for operationalizing social management.

Samantha Hoffman (2019)

Echoing the callback to Mao, the Journal of Public & International Affairs notes:

Since the Mao era, the Chinese government has kept dang’an, a secret dossier, on millions of its urban residents that maintains influence in the public sector to this day. The information included in the dossier ranges from one’s educational and work performance, family background, and records of self-criticism to mental health conditions, but individuals do not have access to their dang’an. When a completely opaque system like dang’an has been in place for decades, an intrusive program like the social credit system may feel less objectionable to the Chinese public.

Journal of Public & International Affairs (2020)

Due to a “regulatory jungle” – where provinces and cities enact different rules – China’s social credit system as a whole is a bit… messy. In a report for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Kendra Schaefer – head of tech policy research at the Beijing-based consultancy Trivium China – describes China’s social credit system as:

...roughly equivalent to the IRS, FBI, EPA, USDA, FDA, HHS, HUD, Department of Energy, Department of Education, and every courthouse, police station, and major utility company in the U.S. sharing regulatory records across a single platform.

Kendra Schaefer (2022)

Yet, while there’s currently no legal or unified definition of its mission, China’s social credit system is still charging ahead – with plans to address its fragmentation problem already underway.

Timeline: How Did China’s Social Credit System Get Started?

The whole idea started back in 1999.

According to Lin Junyue, who led a research team under then-Prime Minister Zhu Rongji:

American companies asked Zhu to create tools to provide them with more information on the Chinese companies they wanted to work with. I made several study trips to the U.S. with my colleagues and we realized that we had to create something even better: a solid system for documenting the creditworthiness of Chinese citizens and enterprises.

Lin Junyue (2019)

Lin and colleagues went on to publish their report, “Towards a National System of Credit Management,” in March 2000. As Lin explains, the term “social credit” followed in 2002, when an official suggested “a lexical symmetry with social security.” That same year, then-President Jiang Zemin promoted the concept during a government address:

We must rectify and standardize the order of the market economy and establish a social credit system compatible with a modern market economy.

President Jiang Zemin (2002)

Now, Jiang’s initial comments focused on social credit in the context of business – which is an important distinction that often gets missed. Not only did China’s social credit system start with a focus on business, to this day its priorities still skew towards the business world. Meaning that, while – yes – all those stories about individuals losing their ability to purchase plane tickets based on “untrustworthy” behavior are true (more on that in a second), businesses are a bigger target.

As the Mercator Institute for China Studies explains:

From the start, [China's social credit system] had a wide remit to target individuals, enterprises, social organizations, and government organizations... Only Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organizations are exempt. However, the main target group has been companies, in line with the overall policy goal of increasing public trust in commercial products and services and in China’s market economy.

Mercator Institute for China Studies (2021)

After Lin’s initial report, the social credit idea picked up speed in 2007 when the Chinese government published a notice titled, “Several Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on the Construction of a Social Credit System.” The authors stressed the “urgency of accelerating the construction of a social credit system” to “further improve the socialist market economic system and build a harmonious socialist society.” Once again, strong preference was paid to industry priorities; however, “social” references left the door open to targeting individuals (specifically those who exhibit financial “untrustworthiness”).

The next big step came in 2014, when the government published a second notice: “State Council Notice Concerning Issuance of the Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System (2014–2020).” As one researcher explains:

While the 2007 document primarily focuses on a finance credit system, the 2014 document extends to other areas of government regulation. The lack of trustworthiness happens at all levels of Chinese society: shoddy products, irresponsible medical treatment, and poisonous milk powder, etc. It is possible that the government realizes that the root cause of financial fraud lies in the low awareness of keeping trust in general and the low cost of breaking trust and integrity, and has therefore rolled out a comprehensive plan for building a “reputation society” (xinyong shehui), meaning that everyone in the society should keep trust and integrity.

Chris Fei Shen, Digital Asia (2019)

The 2014 document also outlined a lot more details and established a planning phase, which ended in 2020. However, while a number of key mechanisms are now in place (and model cities have been testing for years), as mentioned: There’s still a lot to organize. On November 14, 2022, the National Development and Reform Commission and People’s Bank of China, in conjunction with other top government agencies and departments, issued a draft law “for solicitation of public comments.” The draft version of the “Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Establishment of the Social Credit System” – also called the “Social Credit System Construction Law of the People’s Republic of China” (see English translation here) – has been criticized as creating more questions than answers.

According to MIT Technology Review:

[T]he law stays close to local rules that Chinese cities like Shanghai have released and enforced in recent years on things like data collection and punishment methods — just giving them a stamp of central approval. It also doesn’t answer lingering questions that scholars have about the limitations of local rules.

MIT Technology Review (2022)

As Jeremy Daum, a senior fellow at the Yale Law School Paul Tsai China Center, puts it:

This is largely incorporating what has been out there, to the point where it doesn’t really add a whole lot of value.

Jeremy Daum (2022)

So where does that leave things today?

How Does China’s Social Credit System Work?

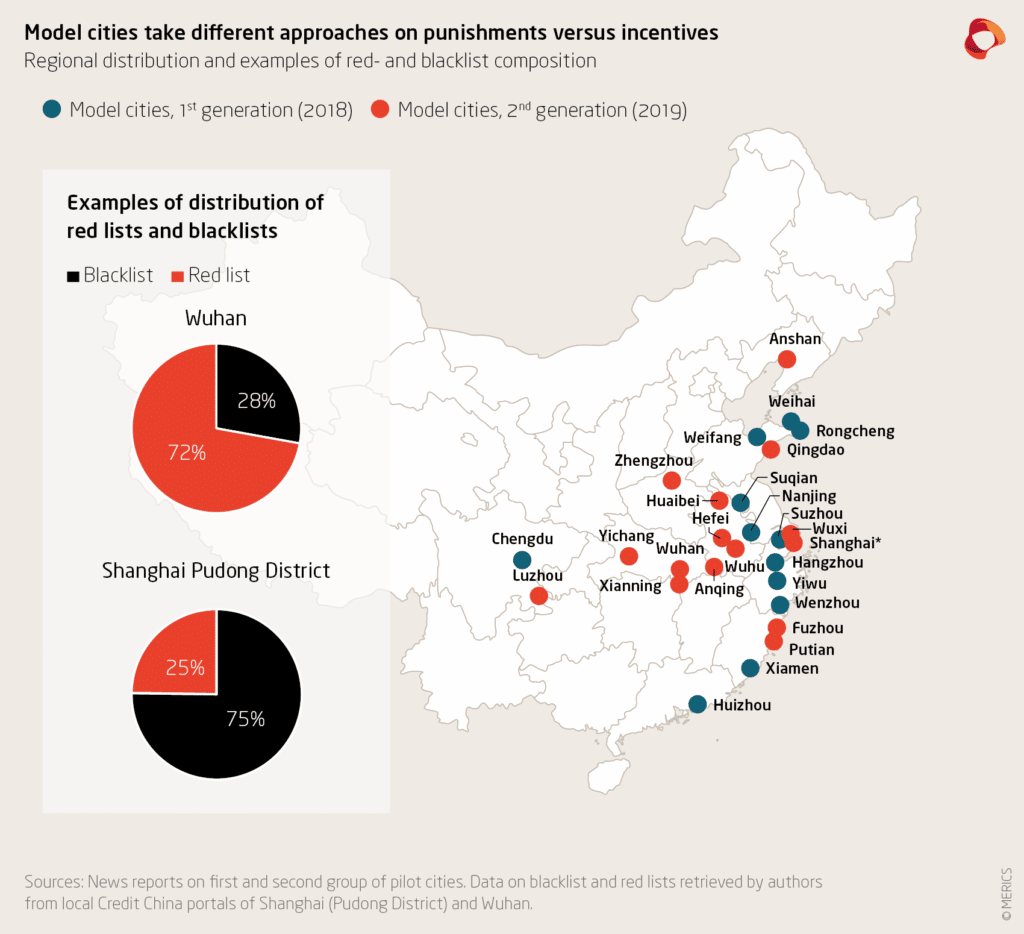

Since 2014, 43 Chinese cities have launched social credit pilot programs. Between 2018-2019, 28 model cities were selected as testing sites for national implementation. In an aptly titled summary (“Fragmentation is the Name of the Game”), the Mercator Institute for China Studies explains:

Although central guidance ensures that the framework remains broadly similar at national and local levels, variations occur as agencies charged with implementing the system at all levels specify this according to local priorities and practices.

Mercator Institute for China Studies (2021)

Add to the mix 47 institutions (with “partly conflicting intentions”) shaping the system from the top – including the State Council, National Development and Reform Commission, and the People’s Bank of China – and you can imagine just how different variations can get.

For instance, while all participating cities adhere to a general black list/red list framework (to identify negative and positive behaviors, respectively), each takes a different approach – with Wuhan and Shanghai Pudong District illustrating almost perfecting inverted emphasis on punishment versus incentive. (Black list distribution in Shanghai Pudong District is 75%, with a red list distribution of 25%; Wuhan’s red list distribution is 72%, with a black list total of 28%.)

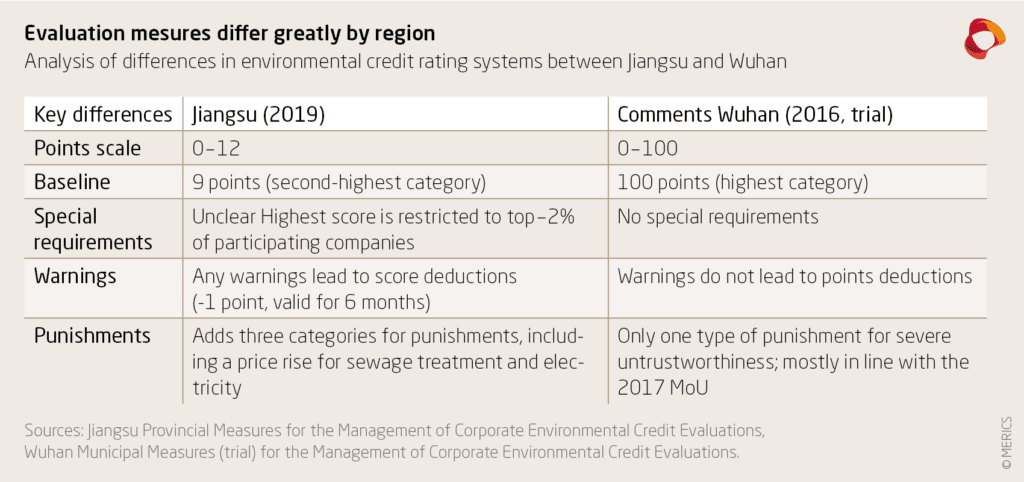

Importantly, there’s no universal point system – yet (an angle that is widely misrepresented in Western reporting). However, point systems do exist (just at the city/province level). Businesses and individuals are rewarded and penalized based on various measures of “trustworthiness.” And, just like the point systems themselves, these measures differ from city to city.

For instance, Jiangsu’s point system runs from 0-12, while Wuhan’s ranges from 0-100. In Jiangsu’s system, any warning leads to a score deduction; in Wuhan, warnings don’t require deductions.

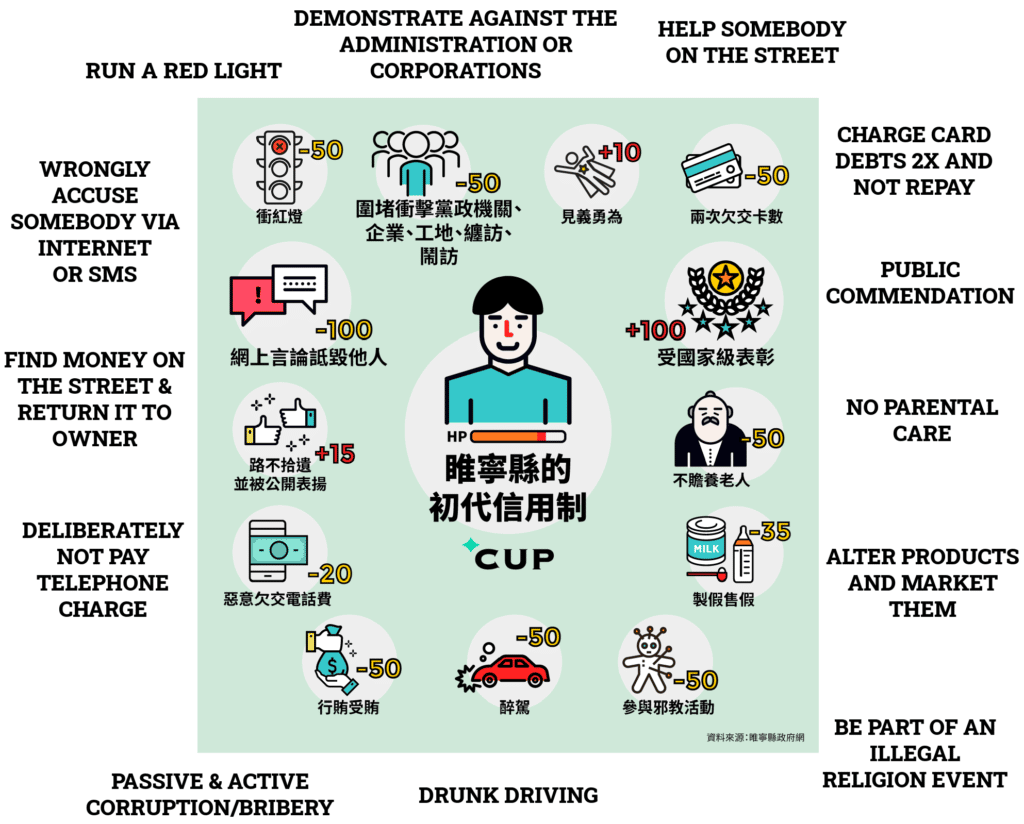

In another example – as reported by one Chinese outlet – Suining County’s social credit pilot program assigned residents 1,000 basic points with extra points for good behavior and negative points for bad behavior. The chart below highlights behavior/point examples (e.g., finding money on the street and returning it: +15 points, running a red light: -50 points).

In 2013, when talk surrounding the social credit system was just picking up speed, Rongcheng set up a program that resulted in “a noticeable change in behavior and social interactions.” As reported by The Nation:

Each citizen starts with an A rating and a capital of 1,000 points. As they earn or lose points, they climb to A+ or fall to B, C, or D. The loss of just one initial point is enough to slide into a B rating, meaning refusal of a mortgage. People get their ratings as a stamped certificate from the new city hall.

The Nation (2019)

The same publication reports:

In July 2018 everybody in the village of Dongdao Lu Jia got a scoring handbook with 12 pages; pruning a neighbor’s tree earns one point, as does taking an older person to hospital or the market (limited to two trips a month). Getting a car out of a ditch is worth one point, helping to read a water meter or lending tools half a point. Letting chickens out of their coop means a 200 yuan ($29) fine and a loss of 10 points; getting into a fight a 1,000 yuan ($147) fine and 10 points; throwing waste into the river 500 yuan ($73) and five points; graffiti or posting stickers hostile to the government, 1,000 yuan and 50 points. The penalties are harsher still for anyone petitioning the upper echelons of government without going through the village head: a fine of 1,000 yuan and an automatic assignment to category B.

The Nation (2019)

As explained by Chinese leadership:

A social credit system is an important component part of the Socialist market economy system and the social governance system. [...] Its inherent requirements are establishing the idea of a sincerity culture, and carrying forward sincerity and traditional virtues, it uses encouragement to keep trust and constraints against breaking trust as incentive mechanisms, and its objective is raising the honest mentality and credit levels of the entire society.

General Office of the State Council (2014)

To shape the idea that “keeping trust is glorious and breaking trust is disgraceful,” China’s 2014 planning document lists a number of focal points regarding both business and personal life (spoiler alert: pretty much everything under the sun is covered). While there’s no centralized list of good versus bad behaviors, participating cities have used this document to guide development of their own rules.

Still, regardless of any point/behavior differences, all programs operate under the same premise:

The system is currently designed to function as a data-powered public shaming and interactive propaganda platform.

Journal of Public & International Affairs (2020)

So what happens when you do something wrong?

Bad Score Penalities: Blacklist

When it comes to the social credit system, China’s policy is clear:

If trust is broken in one place, restrictions are imposed everywhere.

Chinese Communist Party (2016)

Public shaming plays a large part. In 2019, The Nation reported that, in Teng Jia, the names of those who got negative points were broadcast by loudspeaker every Friday. Economic offenders were also called out on the public website, CreditChina.gov.cn (although, at the time of publication, the site is not working).

In 2016, China’s Central Committee and State Council General Offices suggested that the social credit system subject “untrustworthy” citizens to restrictions on:

- Riding trains and aircraft

- Visiting hotels and restaurants

- Children attending high-fee schools

- Building or expensively renovating housing

- Purchasing insurance with a cash value

- Participating in foreign group travel organized by travel agencies

- Working in high management positions

- Serving in the military or Chinese Communist Party

- Working in drug or food sectors

- Using State-owned woodland, grassland, and natural resources

As reported by South China Morning Post, in 2019 the National Development and Reform Commission confirmed the sale of 20.47 million plane tickets and 5.71 million train tickets were stopped due to China’s social credit system.

In one striking example, Liu Hu, a journalist in China who covers censorship and government corruption, was placed on a “List of Dishonest Persons Subject to Enforcement by the Supreme People’s Court” – meaning he couldn’t buy property, plane tickets, or take out a loan. According to Liu:

There was no file, no police warrant, no official advance notification. They just cut me off from the things I was once entitled to. What's really scary is there's nothing you can do about it. You can report to no one. You are stuck in the middle of nowhere.

Liu Hu, Journalist (2011)

In another example, a citizen in Anqing was backlisted during COVID for “causing panic” by posting a video of an ambulance taking away a suspected COVID patient. The move was widely criticized, even within Chinese press.

Businesses also bear a large burden. The same document recommends establishing “blacklist systems and market withdrawal mechanisms in all sectors” and “ensuring that those breaking trust are constrained in their market interactions.” In 2021, the State Administration for Market Regulation published a draft law for managing “untrustworthy enterprises with serious violations.”

According to the European Chamber of Commerce in China:

For every negative rating a set of sanctions is already in place. In case of a blacklisting, a comprehensive list of joint sanctions applies. [...] Sanctions are not limited to penalty fees or court orders. They also include higher inspection rates and targeted audits, restricted issuance of government approvals (e.g. land-use rights and investment permits), exclusion from preferential policies (e.g. subsidies and tax rebates), restrictions from public procurement, as well as public blaming and shaming. Sanctions can even personally affect the legal representative and key personnel of a company.

European Chamber of Commerce in China (2019)

Oh, and word to the wise: Be careful who you trust. The Chinese government also encourages “rewarded reporting systems for acts of breach of trust.” On the business side, companies are tasked with “continuously monitoring their partners’ trustworthiness across the entirety of their business network.”

If you find yourself on a Chinese blacklist, getting off might be tricky. As the South China Morning Post reports, individuals or businesses who have been blacklisted for minor offenses can appeal their status after repaying their debt and/or maintaining a good credit score for a certain period of time. Likewise, the Mercator Institute for China Studies notes that certain offenses are automatically cleared after a determined time period. However, in 2019, Lian Weiliang, deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission, warned:

When we discuss restoring credit, it's mainly aimed at minor or regular offenses. Those who have committed serious offenses or violations will not be taken off the blacklist... their untrustworthy record will be kept for a long time, according to law.

Lian Weiliang, NDRC (2019)

Not surprisingly, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang is quoted as saying:

Those who lose credibility will find it hard to make a tiny step in society.

Premier Li Keqiang (2018)

High Score Rewards: Red List

If the government deems you or your business “trustworthy,” Chinese leadership recommends the social credit system:

Grant rewards to enterprises and model individuals keeping trust according to regulations, broadly propagate them through news media, and forge a public opinion environment that trust-keeping is glorious.

General Office of the State Council (2016)

For instance, in certain regions, volunteering or remaining debt-free could get your name on the red list. Sample rewards include public acknowledgement, prioritized healthcare, and deposit-free renting of public housing. (Unfortunately, a 2019 report suggests reward mechanisms are “less developed” than sanctions.)

In one striking example, people visiting a woman in Rongcheng – who suffered from a nerve disease – earned four points each. As one publication somewhat humorously notes, “Sometimes they bring trays of Chinese dumplings, which Ma’s husband freezes.”

According to the European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies:

China's social credit system inventor Lin says that, instead of the state imprisoning people, under the social credit system, community members nudge them towards expected behaviors.The main motivating factor is patriotism. In school and university education one of the lessons is that the People's Republic of China has had to overcome 150 years of oppression by the West to return now to the world power. Privileges and honors are conferred on citizens with high scores [including posters of "model citizens"].

European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies (2021)

Scarier Systems On the Rise

China’s social credit system – part of Xi Jinping’s vision for “data-driven governance” – doesn’t show any signs of slowing down. In 2020, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Youth League released a music video featuring Chinese pop stars promoting the program. The song, “Live Up to Your Word,” has been described by the Taiwan Times as “bordering on the absurd with the forced smiles of the actors giving the performance a somewhat Orwellian feeling.” (Watch the full video here )

While plenty of Western reports misrepresent China’s social credit system as a unified, national program worthy of wide-scale panic, other U.S. headlines are decidedly less… concerned. (See: “China’s Social Credit System Is Actually Quite Boring.”) Regardless, it’s hard to dispute the argument that China’s social credit system has “triggered global concerns around the ethics of big data.”

And yet, the most disturbing part about the whole program may just be that it distracts from even scarier initiatives under way. For instance, Human Rights Watch reports:

Chinese authorities in Xinjiang are collecting DNA samples, fingerprints, iris scans, and blood types of all residents in the region between the age of 12 and 65.

Human Rights Watch (2017)

The biometric collection program is outlined in a government document titled, “The [Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous] Region Working Guidelines on the Accurate Registration and Verification of Population.” For a full summary of the atrocities being committed against the Uyghur population in China – including torture and “vocational and educational training centers” (that amount to little more than forced labor and imprisonment) – all facilitated by high-tech surveillance, see the United Nation’s 2022 report: “Office of the High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR) Assessment of Human Rights Concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China.”

According to the European Journal of International Studies:

With more than 800 million cameras installed by 2020, there is one surveillance camera for every two Chinese. The surveillance accompanies the citizens throughout the day, from home to work, on the street and in public place, on company floors, in the office, and in university classrooms. So far, Han-Chinese citizens can still (at least) expect not to be filmed while asleep and in the toilet, but the police regulation for Uyghurs in education camps already requires 24/7 taping.

European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies (2021)

Additionally:

Eye-witnesses report that upon registration for an education camp, they are [Uyghurs] are asked to perform in front of a camera for a long time, including making grimaces, walking around and reading out a prepared text for half an hour. These actions enable an artificial intelligence to identify them not just by face recognition, but also by their movements, voice, etc.

European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies (2021)

China is also pioneering the development of “smart cities,” which – with their reliance on data-collection and technology-controlled access features – have raised their own concerns. (For a review, see: “China’s Smart Cities Development” prepared on behalf of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.)

With these initiatives in mind, it’s obvious that China’s social credit system is just one small piece of a much larger, technological puzzle that threatens to deprive Chinese citizens of far more than basic privacy. Summarized by the Mercator Institute for China Studies:

[T]he party state’s ambitions remain clear: To expand, integrate and analyze existing data sources to improve and consolidate Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rule. Despite current fragmentation, this also spells the way forward for the continued evolution of the Social Credit Score System.

Mercator Institute for China Studies (2021)

LIKE THIS ARTICLE? SHARE WITH YOUR FRIENDS:

References

View this post on YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram. You can also listen to a summary via podcast.

Atha, K., Callahan, J., Chen, J., Drun, J., Green, K., Lafferty, B., McReynolds, J., Mulvenon, J., Rosen, B., & Walz. E. (2020). China’s Smart Cities Development. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

Bartsch, B. & Gottske, M. (n.d.). China’s Social Credit System. Bertelsmann Stiftung.

Brusse, V. (15 September 2021). China’s Social Credit System Is Actually Quite Boring. Foreign Policy.

Chinese Communist Party Central Committee General Office and State Council General Office. (2016). Opinions concerning Accelerating the Construction of Credit Supervision, Warning and Punishment Mechanisms for Persons Subject to Enforcement for Trust-Breaking. Accessed via China Copyright and Media (Ed. Rogier Creemers).

Cho, E. (2020). The Social Credit System: Not Just Another Chinese Idiosyncrasy. Journal of Public & International Affairs (Princeton University).

DeAeth, D. (2019). China Releases Pop Anthem to Promote Dystopian ‘Social Credit System’. Taiwan News.

Drinhausen, K. & Brussee, V. (2022). China’s Social Credit System in 2021: From Fragmentation Towards Integration. Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS).

Donnelly, D. (3 January 2023). China Social Credit System Explained – What is it & How Does it Work?. Horizons.

European Chamber of Commerce in China. (2019). The Digital Hand: How China’s Corporate Social Credit System Conditions Market Actors.

Fei Shen, C. (2019). Social Credit System in China. Digital Asia, 21-31.

Feng, J. (22 December 2022). How China’s Social Credit System Works. Newsweek.

General Office of the State Council. (2014). State Council Notice concerning Issuance of the Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System (2014-2020). Accessed via Stanford University: DigiChina.

General Office of the State Council. (2007). Several Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on the Construction of a Social Credit System.

Human Rights Watch. (13 December 2017). China: Minority Region Collects DNA from Millions.

KaRoy & TFBOYS. (2020). Live Up To Your Word. YouTube.

Kuo, L. (1 March 2019). China Bans 23m From Buying Travel Tickets As Part of ‘Social Credit’ System. The Guardian.

Lee, A. (2019). China’s Credit System Stops the Sale of over 26 million Plane and Train Tickets. South China Morning Post.

Lee, A. (2020). What is China’s Social Credit System and Why Is It Controversial?. South China Morning Post.

Jones, K. (18 September 2019). The Game of Life: Visualizing China’s Social Credit System. Visual Capitalist.

Office of the High Commission for Human Rights. (31 August 2022). Assessment of Human Rights Concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China.

Raphael, R. & Xi, L. (2019). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of China’s Social-Credit System. The Nation.

Rosas, A. (26 August 2021). What To Know About China’s Smart Cities and How They Use AI, 5G, and IoT. The China Guys.

State Administration for Market Regulation. (2021). Measures for Managing the List of Untrustworthy Enterprises with Serious Violations (Draft Revisions for Solicitation of Public Comments). Accessed via China Law Translate.

National Development and Reform Commission and People’s Bank of China. (14 November 2022). Law of the PRC on the Establishment of the Social Credit System (Draft Released for Solicitation of Public Comments). China Law Translate. See Chinese version here.

Van Wyk, B. (6 October 2022). The Chinese Start-Ups Working on Developing Smart Cities. The China Project.

Von Blomberg, M. (2018). The Social Credit System and China’s Rule of Law. Mapping China Journal, 2, 77-162.

Woesler, M., Kettner, M., Warnke, M., & Lanfer, J. (2021). The Chinese Social Credit System. Origin, Political Design, Exoskeletal Morality and Comparisons to Western Systems. European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies, 2, 7-35.

Yang, Z. (22 November 2022). China Just Announced a New Social Credit Law. Here’s What It Means. MIT Technology Review.

Zemin, J. (2022). Report at the 16th National Congress of the Communist Party of China. Accessed via China Through a Lens (“Full Text of Jiang Zemin’s Report at the 16th Party Congress”).

Zou, S. (2021). Disenchanting Trust: Instrumental Reason, Algorithmic Governance, and China’s Emerging Social Credit System. Media and Communication, 9(2), 140-9.